by Chris

|

| A 3D model of the One Ring (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

We have just come to pass Bilbo’s and Frodo’s birthdays—September 22 (two weeks ago today, as it happens). It was not long after that Frodo embarked on his quest to destroy the One Ring, beginning what is one of the most famous epic journeys in the history of fiction. It took him a solid thirteen months to make it there and back (so to speak), getting lost, stabbed, poisoned and mutilated along the way.

Amazon affiliate links are used on this site.

The funny thing is, for a tome as great and epic as The Lord of the Rings, thirteen months doesn’t seem like a particularly long time. (Yes, the book starts with a gap of seventeen years between Bilbo’s disappearance and Frodo’s embarkation, but the main events transpire well after this.) One would expect a story of such vast proportions to span lifetimes, and while it does through some of the histories recounted within it, the main action takes place in slightly over a year. Take Beowulf, for example—one of the oldest English-language tales in existence. The action of Beowulf, though not starting with the titular character’s birth, does span the remainder of his life, a period of some fifty years or so (although most of those fifty years are arguably uneventful).

Other epics, such as

Doctor Zhivago (which I briefly mentioned last month), do indeed span decades in time. So do some sci-fi epics like Dune, whose entire series eventually spans millennia. As I wrap up the drafting stage of the third book in my own epic series, this has given me pause to wonder—what exactly makes a story epic?

The Meaning of Epic

The dictionary defines epic as “heroic or grand in scale or character”. My son defines it as better or worse than average (e.g. an epic fail). I suppose the two aren’t that dissimilar, but it raises the question: what counts as epic?

One of the common characteristics of epic fiction is that it involves great tracts of time. Herein fall stories such as those mentioned previously, as well as series such as The Wheel of Time, or James Blish’s

Cities in Flight. Sometimes we are introduced to characters who, through immortality, time travel or some other invention of the author, actually live through these extensive spans of time, experiencing the rise of fall of civilizations, and often losing all they love and hold dear as those around them perish in a more natural length of time. Other times, the story will jump from time to time, introducing new characters along the way, and sometimes leaving behind others who would have naturally perished of old age long before.

But time isn’t the only factor in determining a story’s ‘epicness’; for example, Douglas Adams’

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series spans time from the Stone Age to the end of the universe, but it takes place—from the point of view of the main character, at least—within a comparatively short period of time. In this regard, some might argue that it isn’t really epic at all.

Yet the series, taken altogether, nonetheless leaves the reader with a sense of epicness by the end, simply for the sheer number of traumas and events Arthur Dent survives amongst its pages. From losing his planet to losing his only love, and eventually the entire set of multiverses in which he exists, the main character suffers enormously, which perhaps helps add to the definition of epic: enormous or great suffering, as well. This perhaps ties into the ‘heroic’ aspect of the epic tale, in the sense of a hero being someone who is intended to suffer and yet remain courageous throughout.

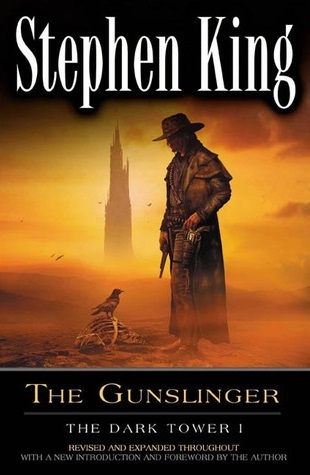

Other stories, such as Stephen King’s The Dark Tower series, feel epic for yet another reason: the sheer length of the volumes themselves. While the first book,

The Gunslinger, is of a more respectable length (around 200 pages), the series gets longer as it goes on, reaching nearly 900 pages by the penultimate (or final, depending on your point of view) novel,

The Dark Tower—leaving the reader having slogged through over 4,000 pages and a million words before the end.

And of course, there are stories that are universally agreed to be epic, yet bear none of these characteristics; Star Wars, for example, is almost always spoken of as an epic tale of good versus evil, yet neither spans great lengths of time nor is particularly long—each movie is a pretty average two hours in length. While the characters suffer losses, they also achieve greatness. But Star Wars’ epic nature might be down to something else: its impact on modern culture. Perhaps no other story is as widely recognized or loved in the modern world—even if you manage to find someone who hasn’t seen it, you’d be hard-pressed to find someone who hasn’t heard of it, whereas even sci-fi greats like Dune or fantasy keystones like The Lord of the Rings tend to be beloved within their genres, but less known by those who don’t follow those areas of fiction (or fiction in general).

Journeys in Space and Time

One universal truth of epic stories, generally, is that the protagonist must undertake a great journey. For some stories, the tale is the journey: The Lord of the Rings is essentially the story of Frodo’s journey from the Shire to Mordor and back again (even its predecessor,

The Hobbit, literally subtitles itself as There and Back Again). Whilst there are many other events that take place, and other major characters travel less (or not at all), physical travel is a key aspect of most epic stories.

Sometimes, this travel is undertaken with a purpose; Frodo sets out with the specific task of first protecting, and then destroying, the One Ring. Other stories are less clear; in the beginning of The Dark Tower series, Roland is pursuing the Man in Black; what he does after he catches up to him is ambiguous, and it’s only later in the series that the concept of reaching the Dark Tower and saving the universe (which turns out to be Stephen King’s collective fictional universe, which himself as the creator) is born.

In my own fantasy series,

The Redemption of Erâth, the main characters set out with no purpose at all—exiled from their homeland, they initially are simply trying to survive. I’m still not certain, with the ongoing development of the series, whether there is going to be a larger journey with a destination in mind, or if the journey is going to be of a more spiritual nature.

Journeys in time equally count: from

The Time Machine to

The Time Traveller’s Wife, many, many stories that take place over decades or centuries, as mentioned before, leave the reader with a sense of epic journeys—even if the action takes place in a single setting. In

The Time Machine, for example, the characters scarcely leave the environs of the time machine itself, despite traveling millions of years into the past and future. In Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander (though perhaps more romance than epic), Claire travels between the 1940s and the 1790s, creating parallel lives in each era.

The Emotional or Spiritual Journey

Another journey that is sometimes overlooked in epic stories is the inner journey: when the character perhaps doesn’t travel much of anywhere in time or place, yet undergoes a dramatic transformation within themselves.

Going back to my own fantasy series (without giving too much away!), this is something I’m considering with my main character, Brandyé; although there is travel across the lands of Erâth and throughout the history of the world, the journey Brandyé takes from an innocent child to a grown man wracked with torment and despair, is perhaps even more important and vital to the story. Paralleling my own emotional growth in life, I have yet to decide if Brandyé will even escape the darkness that haunts him—or if he will succumb, becoming the villain of his own story.

Character transformations can sometimes feel just as epic as great journeys, and sometimes can be the reason a story feels epic in the first place. Although at the end of The Lord of the Rings we feel exhausted after all that has come before, the utter sense of loss in Frodo’s inability to reintegrate into his old life is really the final nail in the coffin: the knowledge that, for him, nothing will ever be the same. So we are sad and devastated to see him leave into the West, yet knowing that it is as final an ending as there could possibly be.

Of course, it could be argued that all stories absolutely rely on character transformation; without growth or change in the protagonist, or at least in the antagonist, there is little to keep our interest throughout. In fact, one could make a list of the worst stories or films based almost solely on this criteria; if no one is better or worse by the end, what was the point of the journey in the first place?

Yet some stories rely on this more heavily, and these are the ones that remain with us longer, make us feel deeper, and truly have a sense of epicness about them. My favorite book of all time,

Great Expectations, although in some ways doesn’t necessarily fit this criteria perfectly, always feels epic to me: the spiritual journey of a young boy who is abused and manipulated throughout his life and only at the very end realizes that he can be himself, is to me an exquisite example of character growth and development. Even the secondary characters such as Estella grow and change, eventually learning that there are better ways to live.

The Traveler

Naturally, a journey of any kind—in time, in space or in spirit—requires a traveler to undertake that journey. This is perhaps the final aspect of what defines a story as epic: who the traveler is, how the react to events, and—as mentioned—how they change as a result.

Some stories take a somewhat predictable approach, naturally, of creating characters who are humble in origins, make their way through danger and difficulty, and arise to the top—either in status or happiness, before either ending there or falling once more into the abyss (whether you’re describing comedy or tragedy, I suppose). Sometimes it’s the reverse: a character high in status is brought low, and has to work their way back (rags to riches, etc.).

I personally prefer stories where the protagonist is less predictable, where you’re not entirely certain if they’re going to do the right thing at any given moment. The wayward traveler is a wonderful device for this, because of course despite (usually) being forced onto a journey unexpectedly, they may or may not have any desire to remain on that path. Frodo is a poor example of this: although he didn’t particularly want to go all the way to Mordor, once he set his mind to it, he went through single-mindedly and determinedly all the way (except for a brief stumble at the end).

A better example comes toward the end of the first Dark Tower book,

The Gunslinger, when Roland is holding Jake over a pit and deliberately drops him to continue his chase of the Man in Black. This is a difficult decision to come to terms with as a reader, but in this sense Roland is very much against the right decisions—an anti-hero, of sorts

Either way, of course, we need a traveler—or several—for epic journeys, and it must take a great deal of time, or effort, to achieve the final goal. When it comes to epic stories, perhaps the only true measure of its ‘epicness’ is how exhausted we feel at the end of it; did we just sprint a hundred yards, or run a marathon (or two)? And this isn’t to say that the marathons are better; sometimes we just need a walk in the park. But there is a genuine sense of satisfaction in completing a story that spans novels, decades and thousands of miles, and without these epic tomes, the world of fiction would probably be a lot more boring.

What are your favorite epic stories, and what makes them epic to you? Let me know in the comments!

Raised between the soaring peaks of the Swiss Alps and the dark industrialism of northern England, beauty and darkness have been twin influences on Chris's creativity since his youth. Throughout his life he has expressed this through music, art, and literature, delving deep into the darkest parts of human nature, and finding the elegance therein. These themes are central to his current literary project, The Redemption of Erâth. A dark epic fantasy, it is a tale of the bitter struggle against darkness and despair, and an acknowledgment that there are some things the mind cannot overcome. Written from a depth of personal experience, Chris' words are touching and powerful, the hallmark of someone who has walked alone through the night, and welcomes the final darkness of the soul. However, for now, he lives in New Jersey with his wife and eleven-year-old son. You can also find him at http://satiswrites.com.

Get even more book news in your inbox, sign up today! Girl Who Reads is an Amazon advertising affiliate; a small commission is earned when purchases are made at Amazon using any Amazon links on this site. Thank you for supporting Girl Who Reads.

.png)